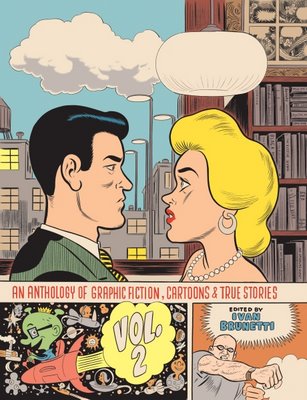

Two years after editing An Anthology of Graphic Fiction, Cartoons, & True Stories for Yale University Press, Chicago comic-book artist Ivan Brunetti has put together another collection of the genre’s most groundbreaking work. Volume 2 comes out from Yale on Oct. 21, featuring 75 contemporary artists such as Art Spiegelman, Chris Ware, Charles Burns, and Gary Panter, along with some classic comic strips. It’s a diverse collection showing the incredible range of this art form.

Two years after editing An Anthology of Graphic Fiction, Cartoons, & True Stories for Yale University Press, Chicago comic-book artist Ivan Brunetti has put together another collection of the genre’s most groundbreaking work. Volume 2 comes out from Yale on Oct. 21, featuring 75 contemporary artists such as Art Spiegelman, Chris Ware, Charles Burns, and Gary Panter, along with some classic comic strips. It’s a diverse collection showing the incredible range of this art form.

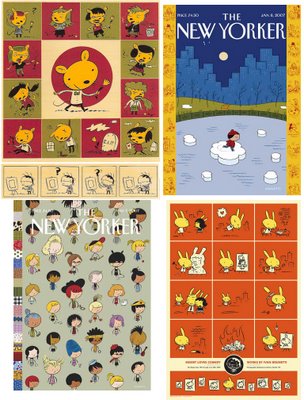

Brunetti, who teaches at Columbia College and the University of Chicago, plumbed the depths of self-loathing in his own disturbing early comics, including four issues of Schizo. Brunetti still has a dark and twisted sense of humor, but he showed his mellower side with two New Yorker covers last year. He is working on an expanded version of his 2007 instructional booklet Cartooning: Philosophy and Practice. Meanwhile, Hoh!, a book of his one-panel gags, will be published next spring. In an interview, Brunetti spoke with me about how he streamlined his drawing style and learned lessons from Charlie Brown and Nancy.

Q: Your characters sometimes resemble Charles Schulz’s characters, with their oversize heads. Was Peanuts an influence?

A: That was definitely the first comic strip I deeply connected to. I grew up in Italy and there were a lot of Disney comics. I didn’t really read Peanuts until I was eight years old and we came to America. I just connected to it on a much more visceral level, I think. I never totally identified with Mickey Mouse or Donald Duck in the way I did with Charlie Brown. It was just very different. It was like directly tapping into my brain or something. It just seemed like real people, in a way that I knew a talking mouse wasn’t. Even the visual of it, the aesthetic, I still think of that as the ideal. When I see Charlie Brown’s head inside the panel – the proportion of the size of his head to the body to the size of the panel – there’s something that feels right to me.

Q: Is it true that you once tried out for a job doing the Nancy comic strip?

A: Yes. I was a big fan of Nancy. There’s a visual purity to it, a precision. It’s almost like a mathematical equation. I mean, they’re dumb jokes, but they’re almost sublimely dumb. For me it was a real struggle. I’m not even sure what kept me going. It ended up taking four months out of my life. I can tell the pages I did after Nancy and before. I really learned a lot about simplifying my cartooning from studying Nancy so closely.

Q: How has your drawing style changed?

A: After my third issue of Schizo, I was doing a lot of illustration work. I didn’t really enjoy it, so I tried to draw as quickly as possible. I found that those quick drawings actually had more life to them. When I was talking on the phone with the art director, I would make doodles on Post-It Notes and later do a full drawing, but the Post-It Note drawing often was better. It just had more life. I developed a looser style that was actually closer to the way I doodled. But at the same time, I wanted it to be more consistent than my doodles.

Q: How do you come up with your palette for color illustrations and cartoons?

Q: How do you come up with your palette for color illustrations and cartoons?

A: I didn’t know what I was doing, so it just became: Let’s work with a couple of colors. I do like the look of old posters and stuff that was lithographed or screen-printed, or printed with spot colors. I still find myself really drawn to black, red, and yellow, which were basically the colors that were always used in Mickey Mouse posters in the ’30s, which I liked as a kid. I like to make something where you use very limited means and still try to get a full spectrum from that. It’s the same thing with the lines. I’m trying to get the maximum amount of information out of the minimum number of lines – to the point where I’m drawing stick arms and stick legs. What’s important to me there is to get the gesture. It’s probably rooted in my inability to see well. I have very bad eyes. I have no depth perception. Everything is very flat to me. I don’t see the world in 3D. So my comics are kind of colored that way, too. They’re very flat colors. That’s kind of how I see.

Q: How did you come up with the New Yorker cover last year showing little characters wearing all sorts of different clothes?

A: I’m a compulsive list maker. I do it not only with words, but with drawings sometimes. I just started drawing the same person with different clothing, and then it evolved into a making a list of all the different clothing styles. It just started growing from there.

Q: Does the second Yale anthology include sorts of comics you did not include in volume one?

A: There are certain aspects of cartooning that I didn’t focus on so much in the first volume. There’s a satirical tradition, and I’ll show more of that. I have a section on comics as collage. There’s also a lot of aggressively experimental art being done now by younger cartoonists that’s breaking a lot of the rules that even I take for granted.

Buy An Anthology of Graphic Fiction, Cartoons, & True Stories, Volume 2 on amazon.

Buy An Anthology of Graphic Fiction, Cartoons, & True Stories, Volume 2 from Yale University Press.