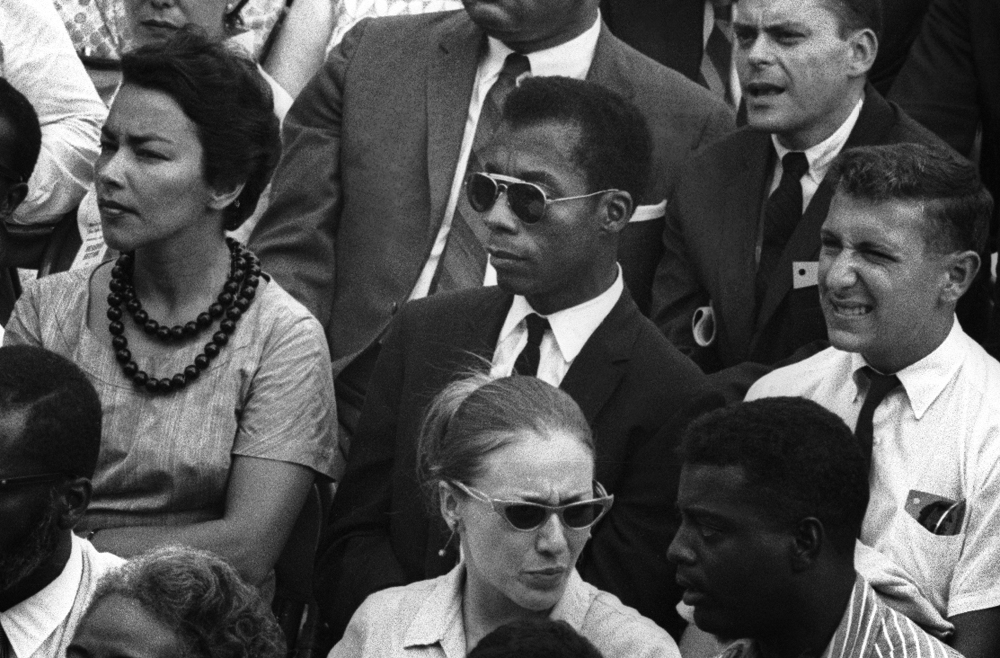

(Photo by DTA Photography (VL) from Flicker.)

(Photo by DTA Photography (VL) from Flicker.)

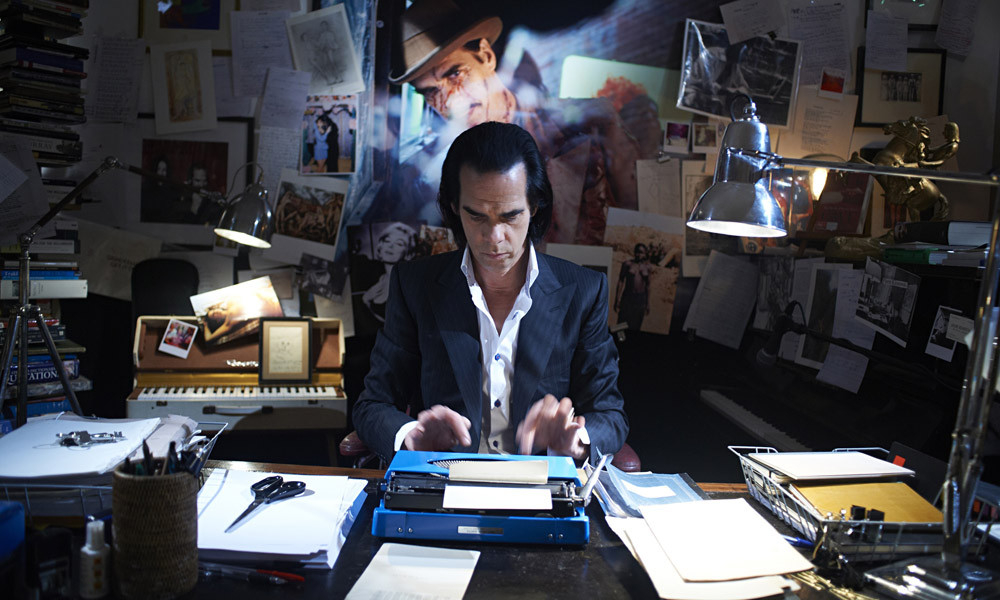

Sitting in a big, red chair in front of the Music Box Theatre’s old red curtains, David Lynch raised one of his hands in a fluttering motion. Those fingers kept twitching as he spoke, answering audience questions after a screening of his new film, “Inland Empire.” The movie is pure Lynch – a three-hour hallucination that perfectly illustrates the dictionary definition of phantasmagoria: “a rapidly changing series of things seen or imagined, as the figures or events of a dream.” After a somewhat coherent first hour, resembling Lynch’s previous film “Mulholland Dream,” the new film disintegrates into one long nightmare. It’s brilliant in many ways, though it’ll tax the patience of some viewers. Just think of it as a restless night of dreams in which you forget where you are and even who you are. And don’t try too hard to figure out what it all means.

Before the film, Lynch introduced musician Daniel Knox, who played an improvisation on the theater’s organ. And then Lynch unfolded a sheet of paper and recited a verse from the Aitareya Upanishad: “We are like the spider. We weave our life and then move along in it. We are like the dreamer who dreams and then lives in the dream. This is true for the entire universe.” After the film, Lynch took a seat and answered questions from his fans. The following is a nearly complete transcript, omitting some of the audience compliments and niceties.

Q: I was wondering why you didn’t work with Angela Badalamenti on this…?

A: I love Angelo Badalamenti like a brother, and I’ve worked with him on many things. It just didn’t happen that I worked with him on this one. He lives in New Jersey, and I live in Los Angeles. Like I always say, if he lived next door to me, it would have been a different thing.

Q: The sound design was fantastic as always… I was hoping you could share your thoughts on sound design.

A: In cinema, there’s many elements rolling along together in time. And so you try to get every element to feel correct based on the idea. And sound … has to marry with the picture, so … the more abstract sound effects and the music all have to work in marriage with the picture. … It’s an experiment based on the feel of the idea.

Q: What inspires you to create what you film?

A: Ideas. Ideas are the thing that drives the boat. And you’re going along, like I always say, and you don’t have an idea, and you don’t have an idea, and then, “Bingo!” There’s an idea. I get a lot of ideas. But sometimes we get an idea that we fall in love with, even if it’s just a fragment of the whole thing. And I fall in love with them because I love the idea, and I love what cinema can do with that idea. And that’s it. And if you get one idea like that and you focus on that, other ideas come swimming along and join it, and the thing emerges.

Q: In your past films, there have been some amazing, colorful cameo appearances, from Henry Rollins in “Lost Highway” to Billy Ray Cyrus in “Mulholland Drive.” I was wondering if you could comment on how these cameos come to, and what is the inspiration behind them?

A: The rule is you try to get the right person for the part. And following that, I see still photos, I work with a woman named Johanna Ray whom I love as the casting director – I work from still photos and then pick out the people that look like they might work, and then meet the people and talk to them. Billy Ray Cyrus, he came in for another, completely different role, and he was videotaped him by Johanna. I’m looking at this videotape and he’s completely wrong for the role he came in for, but I see that he can play Gene the pool man.

Q: Could you share the experience of Richard Pryor in “Lost Highway”?

A: Richard Pryor, we all love Richard Pryor. I don’t know where that came about. I’m so happy that his name came up or somehow I got the idea that he could play the owner of the garage. He was in a wheelchair at that time, but so sharp – unbelievable. You’d just turn him loose and he would riff forever. And so funny. Really great working with Richard Pryor.

Q: I’ve read that you’re optimistic about people, yet many of the characters in your films fail… ?

A: I’m optimistic, for sure. But you know, ideas come for stories and scenes… So a lot of times, there are characters that are failing pretty miserably and others that are doing OK, in a world of contrast, which is a story.

Q: I was wondering if you could talk about the work of Laura Dern.

A: Laura Dern started this whole thing. I was out in front of my house one day, and I look up and I see Laura Dern walking down the sidewalk toward me. She says, “Oh, hello, David,” and I said, “Oh, hello, Laura.” And she said, “I’m your new neighbor.” I hadn’t seen her for a while, and I said, “I’m so happy to hear this, Laura.” She said, “We should do something together again.” And I said, “Yes, we should. Maybe I’ll write something.” That’s sort of what started it. I just thought about her and started writing something. She kind of brought something out. I always say there’s the Laura Dern that lives in Los Angeles, but within her are any number of roles. She can play anything. It’s pretty incredible. I love her like family. And that one meeting started “Inland Empire.”

Q: Laura Dern delivered an excellent performance in this film, and I’m quite surprised she didn’t receive an Academy Award nomination … Do you think it’s a possibility that the Academy voters didn’t see this film?

A: Do I think it’s a possibility that they didn’t see it?

Q: Yeah.

A: Yes. It’s a big possibility. … We were a hair late supplying screeners, but we did supply screeners. I don’t know. You know, sometimes the Academy surprises and gives awards to who we think really deserves it. Other times, they surprise us in the other direction. It’s just, like they say, the way it goes.

Q: You both deserve to be on the red carpet on Feb. 25.

A: You’re a sweetheart.

Q: You were on the Alex Jones show a little while again and you had some questions about the official story of 9/11, and I was wondering if you could comment on that.

A: No. You know, we’re here to talk about “Inland Empire.” But there are many mysteries in life, and that 9/11 is one of them.

Q: Where’s the cow?

A: The cow is in California.

Q: Couldn’t make the trip?

A: It’s hard to travel with a cow.

Q: Were you influenced at all by the films of Krzysztof Kieslowski? I noticed there were a lot of scenes set in Poland.

A: No, I wasn’t.

Q: In an interview about your book, you were talking about fear…

A: Fear is part of negativity. There’s fear – there’s all kinds of words: Anxiety. Depression. Sorrow. Corruption. Violence. Crime. There’s any number of words that make up negativity. With the ability, which we humans have, to dive within, and experience this ocean of pure consciousness, the source of thought, the base of mind, also the base of matter, one giant ocean of pure, vibrant bliss consciousness – if we experience that, that experience enlightens it and we grow in this bliss consciousness. We grow in creativity and intelligence and dynamic peace, energy and power. It’s all right there within us. A side effect of growing in consciousness is negativity begins to recede. They say negativity is just like darkness. And then you say, “Well, let’s look at darkness.” And you see that darkness is nothing. It’s just the absence of something. So when the sun comes up, that light, automatically, without the sun trying, removes darkness. Just like that. This light of unity, this light of pure consciousness, rising up, and negativity begins to recede. It’s a real thing. It’s a real thing. And negativity starts to lift. And so much freedom, so much more flow of creativity comes, from learning a technique that – there are many forms of meditation, but if you are interested in lifting negativity in yourself or lifting negativity in the world, look into this beautiful thing within every human being. Unbounded. Infinite. Eternal. Immortal. Vibrant. Bliss consciousness. It’s there for everybody.

Q: Do you like George Romero?

A: I love George Romero.

Q: My question is a little bit random. What’s your favorite animal and why?

A: Well, you all saw “Inland Empire,” so maybe rabbits. Rabbits are pretty happy.

Q: Thanks.

A: You bet.

Q: I don’t have an arts background. I’m a scientist, but I’ve always appreciated your work.

A: That’s very beautiful. Arts people enjoy science, and sometimes scientists enjoy art.

Q: I read somewhere that a Biblical verse inspired certain parts of the film.

A: No, no, no. That’s “Eraserhead.” In “Eraserhead,” I was maybe two-thirds of the way through, and I hadn’t finished it. The thing was sort of there, but I didn’t know what it meant. I didn’t know what it meant for me. All the parts seemed correct, but overall, I didn’t know what it meant. I was just yearning to know what these ideas were adding up to. And that’s when I got out this Bible and just starting going through it. And lo and behold, there was a sentence, that I said, “That’s it. That’s exactly what this is.” And I closed the thing, and off I went.

Q: With “Mulholland Drive,” you said you had a moment when you didn’t see the ending at first.

A: Yes.

Q: Was there a moment like that in this film?

A: Yes. The analogy is if you are in one room and picture a man in another room, and he’s got a completed puzzle, but he’s popping one piece of puzzle into your room. And that’s the way it is with all things in the beginning – just getting pieces of the thing. And the more pieces you get, maybe sometime along the way, you start seeing something. And then it goes more rapidly from there. It just goes like that on all of them.

Q: Could you talk a little bit about your decision to use digital instead of film on this movie? Was it economic or were there aesthetic reasons, and once you started shooting with digital, did it change the way you went about making the film?

A: Digital. I started making some digital experiments for my Web site with this Sony PD150 camera, which I thought at first was a toy. I kind of liked working with it. It’s easy to work with and you see what you’re getting, and you can go to work and edit it right away. Very beautiful. And I started getting ideas for a scene, after that meeting with Laura. And I started writing the scenes and then shooting them. Getting the idea, writing it and shooting it with the Sony PD150. Not with the idea knowing that it was going toward a feature. So it was a strange way of working. Once more and more of the story started evolving, I saw that it was going to be a feature, but stuck with the Sony PD150, because I didn’t want to change horses in the middle of the stream. We did tests upresing that image and going to film. Although it’s not the quality of film, it has to me its own look, a beautiful look. And every little difference of the medium, it starts talking to you. Ideas seem to come to merit to a certain field that digital was giving. The thing about it, is it’s a small camera. Automatic focus. Forty-minute takes. You see what you get. You’re in a scene with 35mm with a big Panavision camera and a big dolly, and you’re in the scene and nine minutes if the magic is just starting to happen, you have to stop and reload. If you want to turn around, it’s like giant, heavy weight. Huge amount of loss of time. Relighting. So heavy, the lights for film. This is a dream. You go into a scene, you can go deeper and deeper and deeper. Me and the actress go deeper and deeper and deeper and deeper, no interruptions. And maybe a magical thing can happen that wouldn’t have happened otherwise. Digital is the thing. And it’s getting better every day. Film is, as I say, sinking into the La Brea Tar Pits.

Q: The title of the film, “Inland Empire,” also refers to a geographic region in northern Idaho and Washington. I understand you spent some time there when you were a child. Did that affect the way you made the film, and is that just a coincidence with the title?

A: I’ll tell you the story. I was walking to Laura, and this was after we’d gone down the road a little ways. And she said her husband – Ben Harper is her husband – grew up in the Inland Empire, which is an area they call east of L.A. And she went on to talk about where it was and all this, but my mind stopped on this word “Inland Empire.” Even though I’d heard it before, now I’m hearing it afresh. And I stop her, and I say, “That’s the title of this film: ‘Inland Empire.’” And it felt correct. Two weeks later, my brother is cleaning the basement of my parents’ log cabin in Montana and finds an old scrapbook, opens it and sees that it’s my scrapbook from when I was five years old, living in Spokane, Washington. He wraps the scrapbook up and sends it to me. I open it up. And the first picture is an aerial view of Spokane, Washington, and underneath it says, “Inland Empire.” So I had a very good feeling that it was the right title of this film.

(Photo by Joseph Voves from Flickr.)

(Photo by Joseph Voves from Flickr.)

2. WINTER’S BONE (Debra Granik, U.S.)

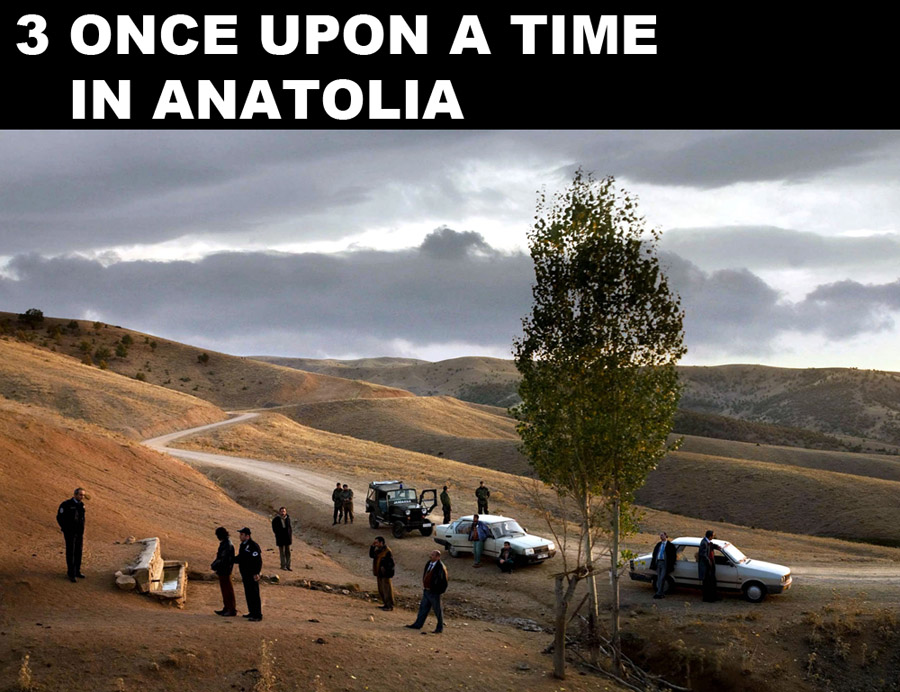

2. WINTER’S BONE (Debra Granik, U.S.) 3. MY JOY (Sergei Loznitsa, Russia)

3. MY JOY (Sergei Loznitsa, Russia)

5. CARLOS (Olivier Assayas, France)

5. CARLOS (Olivier Assayas, France) 6. ANOTHER YEAR (Mike Leigh, U.K.)

6. ANOTHER YEAR (Mike Leigh, U.K.) 7. TUESDAY, AFTER CHRISTMAS (Radu Muntean, Romania)

7. TUESDAY, AFTER CHRISTMAS (Radu Muntean, Romania) 8. THE SECRET OF KELLS (Thom Moore, Ireland)

8. THE SECRET OF KELLS (Thom Moore, Ireland) 9. WHITE MATERIAL (Claire Denis, France)

9. WHITE MATERIAL (Claire Denis, France) 10. BLUEBEARD (Catherine Breillat, France)

10. BLUEBEARD (Catherine Breillat, France)

All the Invisible Things (Heile Welt) – This Austrian film was a real find, a total surprise for me. I hadn’t read any reviews of it. The only reason I went was my interest in Austria and the fact that it was playing at a time when I didn’t have anything else to do. Filmed in Graz (a city I have visited a couple of times, and where I have some cousins), All the Invisible Things is a low-budget, documentary-like drama with overlapping plots and chronologies. It starts off some young nihilist thugs on the run (and at this point in the film, I was thinking it was well-made but almost too depressing to stomach), and then shifts to other stories involving other characters, including some parents of the teens in the first part of the movie. Like Pulp Fiction, The Killing, Exotica, Memento or Amores Perros, it doesn’t reveal how all of the plots connect until the end, but it avoids feeling gimmicky. There’s no resolution at the end, just a deep sense of tragedy. The director, Jakob W. Erwa, was present for the screening, which was, unfortunately, sparsely attended. He’s only 26, I think, and he came across as a modest and creative young man. He talked about starting out with a short film, largely improvised by the young actors, and then developing it into a feature film by wondering about the other stories behind the story. I hope Erwa gets U.S. distribution for this film and continues directing; he shows a ton of promise.

All the Invisible Things (Heile Welt) – This Austrian film was a real find, a total surprise for me. I hadn’t read any reviews of it. The only reason I went was my interest in Austria and the fact that it was playing at a time when I didn’t have anything else to do. Filmed in Graz (a city I have visited a couple of times, and where I have some cousins), All the Invisible Things is a low-budget, documentary-like drama with overlapping plots and chronologies. It starts off some young nihilist thugs on the run (and at this point in the film, I was thinking it was well-made but almost too depressing to stomach), and then shifts to other stories involving other characters, including some parents of the teens in the first part of the movie. Like Pulp Fiction, The Killing, Exotica, Memento or Amores Perros, it doesn’t reveal how all of the plots connect until the end, but it avoids feeling gimmicky. There’s no resolution at the end, just a deep sense of tragedy. The director, Jakob W. Erwa, was present for the screening, which was, unfortunately, sparsely attended. He’s only 26, I think, and he came across as a modest and creative young man. He talked about starting out with a short film, largely improvised by the young actors, and then developing it into a feature film by wondering about the other stories behind the story. I hope Erwa gets U.S. distribution for this film and continues directing; he shows a ton of promise. Control – The photography in this Ian Curtis biopic is absolutely beautiful. That’s not surprising, given that the director is an acclaimed rock-music photographer, Anton Corbijn. Many of the shots in this black-and-white movie have a shallow depth of field, creating a three-dimensional feeling. I also liked the way the film is edited, with a spare, poetic sense of storytelling. I’m no expert on Joy Division or the Manchester music scene, so I’ll leave it up to others to say how authentic Control is, but it felt real to me. The acting performances are strong, the music sounds excellent, and the movie doesn’t stoop to using any cheap psychobabble explanations for why Curtis killed himself.

Control – The photography in this Ian Curtis biopic is absolutely beautiful. That’s not surprising, given that the director is an acclaimed rock-music photographer, Anton Corbijn. Many of the shots in this black-and-white movie have a shallow depth of field, creating a three-dimensional feeling. I also liked the way the film is edited, with a spare, poetic sense of storytelling. I’m no expert on Joy Division or the Manchester music scene, so I’ll leave it up to others to say how authentic Control is, but it felt real to me. The acting performances are strong, the music sounds excellent, and the movie doesn’t stoop to using any cheap psychobabble explanations for why Curtis killed himself. The Man From London (A Londini Férfi) – For me, the most dispiriting part of this year’s film festival was waiting 45 minutes for a CTA el to get me to the theater for the new film by Bela Tarr. Even though I’d left home earlier than usual, I showed up at the theater 15 minutes late, walked into a packed theater and ended up sitting in the front row, craning my neck up at a huge screen. From what I hear, I did not miss much plot exposition, but I still feel like I have to give this film an incomplete grade because of the way I experienced it. Like Tarr’s other films (Werckmeister Harmonies is one of my favorites of the last decade), this one is filled with glacially slow tracking shots and an occasionally opaque plot. It’s also deeply beautiful and mysterious, with a surprising performance by the always great Tilda Swinton – in Hungarian! Based on a Georges Simenon novel, it feels like a film noir as seen by a whale swimming just offshore. Tarr’s films are not easily digested, but I will definitely see this again as soon as I get a chance.

The Man From London (A Londini Férfi) – For me, the most dispiriting part of this year’s film festival was waiting 45 minutes for a CTA el to get me to the theater for the new film by Bela Tarr. Even though I’d left home earlier than usual, I showed up at the theater 15 minutes late, walked into a packed theater and ended up sitting in the front row, craning my neck up at a huge screen. From what I hear, I did not miss much plot exposition, but I still feel like I have to give this film an incomplete grade because of the way I experienced it. Like Tarr’s other films (Werckmeister Harmonies is one of my favorites of the last decade), this one is filled with glacially slow tracking shots and an occasionally opaque plot. It’s also deeply beautiful and mysterious, with a surprising performance by the always great Tilda Swinton – in Hungarian! Based on a Georges Simenon novel, it feels like a film noir as seen by a whale swimming just offshore. Tarr’s films are not easily digested, but I will definitely see this again as soon as I get a chance. Opium: Diary of a Madwoman (Ópium: Egy Elmebeteg Naplója) – This Hungarian film by János Szász includes some difficult viewing. I wouldn’t readily watch it again, but it was an intense and memorable experience. The provocative sex scenes are troubling and discomforting, but also very sensuous.

Opium: Diary of a Madwoman (Ópium: Egy Elmebeteg Naplója) – This Hungarian film by János Szász includes some difficult viewing. I wouldn’t readily watch it again, but it was an intense and memorable experience. The provocative sex scenes are troubling and discomforting, but also very sensuous. Ploy – The few films I’ve seen from Thailand have an odd combination of the mundane and the fantastic. In this movie by Pen-Ek Ratanaruang, the setting – a hotel – is downright generic. The drama that unfolds in this place has some ominous undertones, and Ploy gradually takes surreal turns, with disturbing dreams and a whole subplot that may or may not have happened. In the end, I found it to be an effective exploration of that eternal theme, the difficulty of human connections.

Ploy – The few films I’ve seen from Thailand have an odd combination of the mundane and the fantastic. In this movie by Pen-Ek Ratanaruang, the setting – a hotel – is downright generic. The drama that unfolds in this place has some ominous undertones, and Ploy gradually takes surreal turns, with disturbing dreams and a whole subplot that may or may not have happened. In the end, I found it to be an effective exploration of that eternal theme, the difficulty of human connections. You, the Living (Du Levande) – Roy Andersson is the director of a wonderfully surreal film from a few years back, Songs From the Second Floor, and now he’s back with You, the Living, which feels like a continuation of the previous film. One of the recurring visual gigs (or existentialist black-humor bits) from the first film was this unending traffic jam on a Swedish street, with the motorists trapped in an eternal hell of congestion. Well, in You, the Living, there’s yet another traffic jam. Or is it the same one from the first movie, still going on? There’s also a bit in the new movie in which a musician annoys his downstairs neighbor by practicing on the tuba. Could that be a reference to the title of the earlier film – a song from the second floor? The vignettes in You, the Living are only vaguely connected. They do not all tie together in the end in a nice, neat package, but that was just fine with me.

You, the Living (Du Levande) – Roy Andersson is the director of a wonderfully surreal film from a few years back, Songs From the Second Floor, and now he’s back with You, the Living, which feels like a continuation of the previous film. One of the recurring visual gigs (or existentialist black-humor bits) from the first film was this unending traffic jam on a Swedish street, with the motorists trapped in an eternal hell of congestion. Well, in You, the Living, there’s yet another traffic jam. Or is it the same one from the first movie, still going on? There’s also a bit in the new movie in which a musician annoys his downstairs neighbor by practicing on the tuba. Could that be a reference to the title of the earlier film – a song from the second floor? The vignettes in You, the Living are only vaguely connected. They do not all tie together in the end in a nice, neat package, but that was just fine with me.

Hungarian director György Pálfi made a startling debut with his film “Hukkle,” and now he has proven it was no fluke. His newest movie, “Taxidermia,” which obviously has a much bigger budget, shows that he’s a major talent. “Taxidermia” floored me. That being said, this is one of those movies that has to come with a “not for all tastes” warning sticker. Oh, yeah, let’s add a “not for the faint of heart” label. And while we’re at it: “Stay away from this movie if you cannot stand the sight of vomit.”

Hungarian director György Pálfi made a startling debut with his film “Hukkle,” and now he has proven it was no fluke. His newest movie, “Taxidermia,” which obviously has a much bigger budget, shows that he’s a major talent. “Taxidermia” floored me. That being said, this is one of those movies that has to come with a “not for all tastes” warning sticker. Oh, yeah, let’s add a “not for the faint of heart” label. And while we’re at it: “Stay away from this movie if you cannot stand the sight of vomit.” An earlier film I saw by this movie’s Thai director, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, “Tropical Malady,” was one of the most peculiar films of the last few years. It was hard to figure out exactly what the director was trying to say with “Tropical Malady,” but its odd juxtapositions and some of its surreal images stuck in my mind. With “Syndromes and a Century,” Weerasethakul is playing around with our minds once again. According to a synopsis, the film is supposedly about the director’s parents, who were doctors. But it’s far from being a straightforward memoir. Rather, it’s a series of vignettes, many told with realistic and natural humor. A rural hospital in the first half of the film is followed by an urban hospital in the second half, with many of the same scenes being acted out again – with similar but slightly different dialogue. This creates many moments of déjà vu. And then, at the end, “Syndromes and a Century” drifts off into a beautiful but almost abstract sequence, including a long shot of an air vent blowing steam. I don’t know what it all meant, but I found it mesmerizing, one of the best films I saw at the fest.

An earlier film I saw by this movie’s Thai director, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, “Tropical Malady,” was one of the most peculiar films of the last few years. It was hard to figure out exactly what the director was trying to say with “Tropical Malady,” but its odd juxtapositions and some of its surreal images stuck in my mind. With “Syndromes and a Century,” Weerasethakul is playing around with our minds once again. According to a synopsis, the film is supposedly about the director’s parents, who were doctors. But it’s far from being a straightforward memoir. Rather, it’s a series of vignettes, many told with realistic and natural humor. A rural hospital in the first half of the film is followed by an urban hospital in the second half, with many of the same scenes being acted out again – with similar but slightly different dialogue. This creates many moments of déjà vu. And then, at the end, “Syndromes and a Century” drifts off into a beautiful but almost abstract sequence, including a long shot of an air vent blowing steam. I don’t know what it all meant, but I found it mesmerizing, one of the best films I saw at the fest. Claude Chabrol is back with another thriller that isn’t really a thriller. Some of Chabrol’s films are a little dull, while others hit their mark, including the chilling “La Ceremonie.” He films stories that might have appealed to Hitchcock, but more often than not, films them in a matter-of-fact, almost flat style. This one was no exception. It was rather talky, and by the standards of American legal thrillers, it would probably be considered dull. And yet it really held my attention. Isabelle Huppert is great, as is usually the case (though this role was not quite as peculiar as some of her best performances). As a judge investigating corporate corruption, she is stubbornly determined.

Claude Chabrol is back with another thriller that isn’t really a thriller. Some of Chabrol’s films are a little dull, while others hit their mark, including the chilling “La Ceremonie.” He films stories that might have appealed to Hitchcock, but more often than not, films them in a matter-of-fact, almost flat style. This one was no exception. It was rather talky, and by the standards of American legal thrillers, it would probably be considered dull. And yet it really held my attention. Isabelle Huppert is great, as is usually the case (though this role was not quite as peculiar as some of her best performances). As a judge investigating corporate corruption, she is stubbornly determined. This Australian film is well acted and it’s a fairly well told story, but I couldn’t help wondering if it was worthwhile to sit through another movie about people addicted to drugs. I don’t know that I really found any insights into drug addiction that I haven’t seen in countless other films and stories. This isn’t bad, but nothing to get too excited about. The lead actress, Abbie Cornish, is breathtakingly beautiful and sexy … almost to the point where it distracted me from her fine performance. (OK, OK, I like her, all right?) Heath Ledger also gives a strong performance, and Geoffrey Rush is good in a supporting role.

This Australian film is well acted and it’s a fairly well told story, but I couldn’t help wondering if it was worthwhile to sit through another movie about people addicted to drugs. I don’t know that I really found any insights into drug addiction that I haven’t seen in countless other films and stories. This isn’t bad, but nothing to get too excited about. The lead actress, Abbie Cornish, is breathtakingly beautiful and sexy … almost to the point where it distracted me from her fine performance. (OK, OK, I like her, all right?) Heath Ledger also gives a strong performance, and Geoffrey Rush is good in a supporting role. I wasn’t sure that I really wanted to watch another movie following a woman as she tries to go through with a terrorist plot to blow herself up. (See Santosh Sivan’s film “The Terrorist,” from 1999.) But this was tense and quite effective. It’s clearly filmed on a low budget, but that doesn’t matter, because the filmmakers make excellent use of their limited resources. The terrorist plot is left vague. Who are these people, and why are they sending this young woman to explode herself in Times Square? It doesn’t really matter. The woman seems stoic, though she begins to crack. Is she just a mixed-up young woman who wants to commit suicide, someone who ended up with the wrong people? That’s one possible way of reading the story. Luisa Williams’ performance as the would-be bomber is restrained, almost deadpan at times, but it feels real.

I wasn’t sure that I really wanted to watch another movie following a woman as she tries to go through with a terrorist plot to blow herself up. (See Santosh Sivan’s film “The Terrorist,” from 1999.) But this was tense and quite effective. It’s clearly filmed on a low budget, but that doesn’t matter, because the filmmakers make excellent use of their limited resources. The terrorist plot is left vague. Who are these people, and why are they sending this young woman to explode herself in Times Square? It doesn’t really matter. The woman seems stoic, though she begins to crack. Is she just a mixed-up young woman who wants to commit suicide, someone who ended up with the wrong people? That’s one possible way of reading the story. Luisa Williams’ performance as the would-be bomber is restrained, almost deadpan at times, but it feels real. This is sort of a multicultural, international film, teaming up Thai director Pen-Ek Ratanaruang with Japanese actor Tadanobu Asano, Australian cinematographer Christopher Doyle and Thai screenwriter Prabda Yoon. And many of the characters speak in broken English, seemingly as a way to communicate across Asian cultures. (Or maybe just to make the movie more marketable in the U.S.) While it’s described as a thriller, it’s much more existential and abstract than that. Or maybe it’s just confusing. It sort of drifts along without the driving plot that crime movies usually have. It has its moments, but I found it a little lacking. There are some precious moments of humor involving a low-rent cruise ship.

This is sort of a multicultural, international film, teaming up Thai director Pen-Ek Ratanaruang with Japanese actor Tadanobu Asano, Australian cinematographer Christopher Doyle and Thai screenwriter Prabda Yoon. And many of the characters speak in broken English, seemingly as a way to communicate across Asian cultures. (Or maybe just to make the movie more marketable in the U.S.) While it’s described as a thriller, it’s much more existential and abstract than that. Or maybe it’s just confusing. It sort of drifts along without the driving plot that crime movies usually have. It has its moments, but I found it a little lacking. There are some precious moments of humor involving a low-rent cruise ship. A charming Swiss movie about a child prodigy on piano, which won a decent round of applause at the screening I attended. It’s a heartwarming movie, just quirky enough in places to keep things interesting. It’s the first movie I’ve ever seen that was in Swiss German, with subtitles in English as well as standard German. I remember enough German from college that I was trying to read the German subtitles and figure out how they related to what was being said, which was a little distracting.

A charming Swiss movie about a child prodigy on piano, which won a decent round of applause at the screening I attended. It’s a heartwarming movie, just quirky enough in places to keep things interesting. It’s the first movie I’ve ever seen that was in Swiss German, with subtitles in English as well as standard German. I remember enough German from college that I was trying to read the German subtitles and figure out how they related to what was being said, which was a little distracting. This Iranian film won the festival’s top prize, the Golden Hugo, and it’s a worthy winner. Here’s an oversimplified plot summary: A woman who’s about to get married witnesses some other people in marriages that have gone bad. The story unfolds in a way that’s complex yet never confusing, and like the best of Iranian films, it feels like an honest and realistic portrait of the way people relate to one another.

This Iranian film won the festival’s top prize, the Golden Hugo, and it’s a worthy winner. Here’s an oversimplified plot summary: A woman who’s about to get married witnesses some other people in marriages that have gone bad. The story unfolds in a way that’s complex yet never confusing, and like the best of Iranian films, it feels like an honest and realistic portrait of the way people relate to one another. This is a tricky one to describe in much detail because of the underlying question of whether it’s an actual documentary or a mockumentary. It’s fairly compelling, and even after you think you’ve figured it out, it keeps on raising questions. And for once, a movie made in Chicago looks like it was made in Chicago. “Street Thief” captures the city’s side streets better than any Hollywood film.

This is a tricky one to describe in much detail because of the underlying question of whether it’s an actual documentary or a mockumentary. It’s fairly compelling, and even after you think you’ve figured it out, it keeps on raising questions. And for once, a movie made in Chicago looks like it was made in Chicago. “Street Thief” captures the city’s side streets better than any Hollywood film.

A few DVDs I’ve caught up on recently:

A few DVDs I’ve caught up on recently: